subhas chandra bose

Subhas Chandra Bose (/ʃʊbˈhɑːs ˈtʃʌndrə ˈboʊs/ ⓘ shuub-HAHSS CHUN-drə BOHSS;[12] 23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945) was an Indian nationalist whose defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among many Indians, but his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan left a legacy vexed by authoritarianism, anti-Semitism, and military failure. The honorific Netaji (Bengali: "Respected Leader") was first applied to Bose in Germany in early 1942—by the Indian soldiers of the Indische Legion and by the German and Indian officials in the Special Bureau for India in Berlin. It is now used throughout India.[h]

Subhas Bose was born into wealth and privilege in a large Bengali family in Orissa during the British Raj. The early recipient of an Anglocentric education, he was sent after college to England to take the Indian Civil Service examination. He succeeded with distinction in the vital first exam but demurred at taking the routine final exam, citing nationalism as a higher calling. Returning to India in 1921, Bose joined the nationalist movement led by Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress. He followed Jawaharlal Nehru to leadership in a group within the Congress which was less keen on constitutional reform and more open to socialism.[i] Bose became Congress president in 1938. After reelection in 1939, differences arose between him and the Congress leaders, including Gandhi, over the future federation of British India and princely states, but also because discomfort had grown among the Congress leadership over Bose's negotiable attitude to non-violence, and his plans for greater powers for himself.[15] After the large majority of the Congress Working Committee members resigned in protest,[16] Bose resigned as president and was eventually ousted from the party.[17][18]

In April 1941 Bose arrived in Nazi Germany, where the leadership offered unexpected but equivocal sympathy for India's independence.[19][20] German funds were employed to open a Free India Centre in Berlin. A 3,000-strong Free India Legion was recruited from among Indian POWs captured by Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps to serve under Bose.[21][j] Although peripheral to their main goals, the Germans inconclusively considered a land invasion of India throughout 1941. By the spring of 1942, the German army was mired in Russia and Bose became keen to move to southeast Asia, where Japan had just won quick victories.[23] Adolf Hitler during his only meeting with Bose in late May 1942 offered to arrange a submarine.[24] During this time, Bose became a father; his wife,[6][k] or companion,[25][l] Emilie Schenkl, gave birth to a baby girl.[6][m][19] Identifying strongly with the Axis powers, Bose boarded a German submarine in February 1943.[26][27] Off Madagascar, he was transferred to a Japanese submarine from which he disembarked in Japanese-held Sumatra in May 1943.[26]

With Japanese support, Bose revamped the Indian National Army (INA), which comprised Indian prisoners of war of the British Indian army who had been captured by the Japanese in the Battle of Singapore.[28][29][30] A Provisional Government of Free India was declared on the Japanese-occupied Andaman and Nicobar Islands and was nominally presided by Bose.[31][2][n] Although Bose was unusually driven and charismatic, the Japanese considered him to be militarily unskilled,[o] and his soldierly effort was short-lived. In late 1944 and early 1945, the British Indian Army reversed the Japanese attack on India. Almost half of the Japanese forces and fully half of the participating INA contingent were killed.[p][q] The remaining INA was driven down the Malay Peninsula and surrendered with the recapture of Singapore. Bose chose to escape to Manchuria to seek a future in the Soviet Union which he believed to have turned anti-British. He died from third-degree burns received when his overloaded plane crashed in Japanese Taiwan on August 18, 1945.[r] Some Indians did not believe that the crash had occurred,[s] expecting Bose to return to secure India's independence.[t][u][v] The Indian National Congress, the main instrument of Indian nationalism, praised Bose's patriotism but distanced itself from his tactics and ideology.[w][41] The British Raj, never seriously threatened by the INA, charged 300 INA officers with treason in the INA trials, but eventually backtracked in the face of opposition by the Congress,[x] and a new mood in Britain for rapid decolonisation in India.[y][41][44]

Bose's legacy is mixed. Among many in India, he is seen as a hero, his saga serving as a would-be counterpoise to the many actions of regeneration, negotiation, and reconciliation over a quarter-century through which the independence of India was achieved.[z][aa][ab] His collaborations with Japanese Fascism and Nazism pose serious ethical dilemmas,[ac] especially his reluctance to publicly criticize the worst excesses of German anti-Semitism from 1938 onwards or to offer refuge in India to its victims.[ad][ae][af]

Biography

1897–1921: Early life

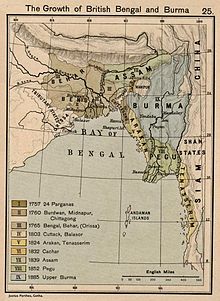

Subhas Chandra Bose was born to Bengali parents Prabhavati Bose (née Dutt) and Janakinath Bose on 23 January 1897 in Cuttack—in what is today the state of Odisha in India, but was then the Orissa Division of Bengal Province in British India.[ag][ah] Prabhavati, or familiarly Mā jananī (lit. 'mother'), the anchor of family life, had her first child at age 14 and 13 children thereafter. Subhas was the ninth child and the sixth son.[54] Jankinath, a successful lawyer and government pleader,[53] was loyal to the government of British India and scrupulous about matters of language and the law. A self-made man from the rural outskirts of Calcutta, he had remained in touch with his roots, returning annually to his village during the pooja holidays.[55]

Eager to join his five school-going older brothers, Subhas entered the Baptist Mission's Protestant European School in Cuttack in January 1902.[7] English was the medium of all instruction in the school, the majority of the students being European or Anglo-Indians of mixed British and Indian ancestry.[52] The curriculum included English—correctly written and spoken—Latin, the Bible, good manners, British geography, and British History; no Indian languages were taught.[52][7] The choice of the school was Janakinath's, who wanted his sons to speak flawless English with flawless intonation, believing both to be important for access to the British in India.[56] The school contrasted with Subhas's home, where only Bengali was spoken. At home, his mother worshipped the Hindu goddesses Durga and Kali, told stories from the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, and sang Bengali religious songs.[7] From her, Subhas imbibed a nurturing spirit, looking for situations in which to help people in distress, preferring gardening around the house to joining in sports with other boys.[8] His father, who was reserved in manner and busy with professional life, was a distant presence in a large family, causing Subhas to feel he had a nondescript childhood.[57] Still, Janakinath read English literature avidly—John Milton, William Cowper, Matthew Arnold, and Shakespeare's Hamlet being among his favourites; several of his sons were to become English literature enthusiasts like him.[56]

Comments

Post a Comment